Few believed, two decades ago, that grimy, depressed Bilbao had what it took to host a world-renowned art museum, but in its first year after opening in a blaze of controversy in 1997, 1.35 million visitors flocked to the Guggenheim Bilbao. Since then the annual number has remained steady at around one million, and the museum has breathed new life into what was once a dying city.

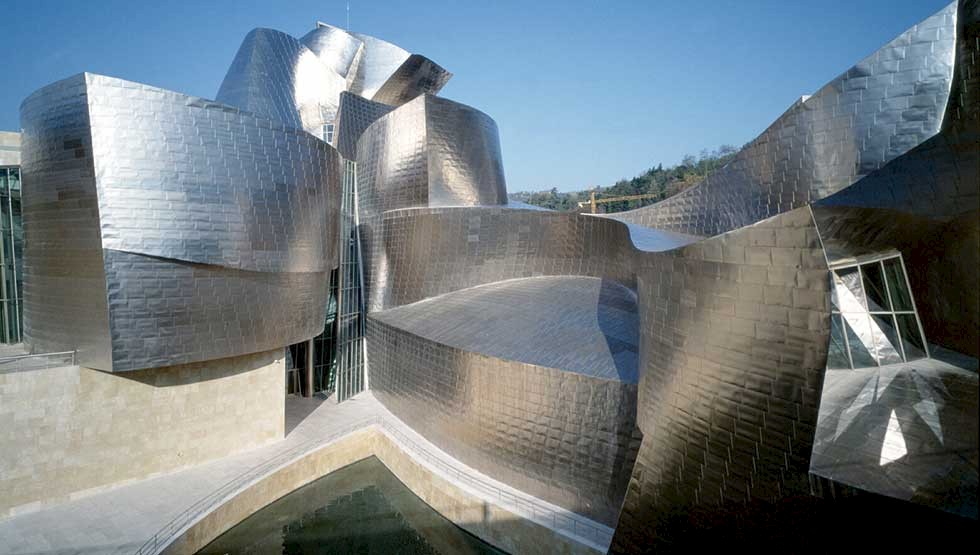

Now the words Guggenheim Bilbao seem to hang together beautifully. There is no contradiction in combining the name of the world-renowned brand of art museums encased in spectacular architecture with that of the gritty, post-industrial Basque city. The proof lies in the millions who since 1997 have made what is now an almost obligatory pilgrimage for the culturally curious to see Frank Gehry’s waves of titanium and the artwork inside. But when the possibility of Bilbao hosting a Guggenheim first arose in the late 1980s, the idea did not strike a harmonious chord with everyone.

Juan Ignacio Vidarte, director general of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, remembers how it all started in a city badly in need of a break, but where the overriding attitude towards such an extravagant idea was one of “scepticism”. With unemployment soaring amidst urban decay, polluted waterways and degraded green spaces, Bilbao hardly appeared to have the right ingredients to attract a flock of international art lovers. Using a cultural project as the driving force behind an economic transformation was an extremely bold idea, something that many observers say has never been pulled off in the same way by any other city in the world.

But what was it about Bilbao’s offer that captured the imagination of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, whose European presence prior to that time was restricted to the glamourous exclusivity of Venice? The Guggenheim Foundation wanted to expand within the continent and Bilbao was at that moment just beginning its own transformation process, with part of that strategy aiming to reinforce its cultural identity in a way that would transcend the Basque region’s image. City representatives recall that the two expansion processes seemed to meld together, despite what at first glance looked like a disconnect between a run-down post-industrial city and such a highbrow cultural institution. It is important to remember that this was still a full decade before the Tate Modern in London would confirm the great potential in combining industrial landscapes with contemporary art. Insiders say that the fact that the museum was seen as a transformational element by the host city weighed heavily on the Foundation’s eventual decision.

“The museum could become a transformational element for the entire city”

Juan Ignacio Vidarte Managing director of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Tweet ThisOther architectural developments along the banks of the Nervion river helped the Guggenheim make a more natural fit. But it was above all the quality of the idea, the uncompromising investment in titanium, glass and limestone, and a brilliantly audacious design which made for a watershed moment in the development of a new Bilbao and the Basque Country brand itself.

The construction of the Guggenheim cost €133 million, half paid for by the regional government and the other half provided by Biscay’s provincial administration. The economic impact, however, was spectacular from the very start as crowds thronged to see outstanding art and also to try and gauge for themselves the architectural and social impact Gehry’s creation had made on the famously harsh Basque city. In its first year, the Guggenheim attracted 1.33 million visitors, three times more than had been expected, making a positive impact on the Basque region’s GDP of €144 million. According to city authorities, the museum paid for itself in a year. It has not stopped shining like a beacon for the Basque Country brand ever since.

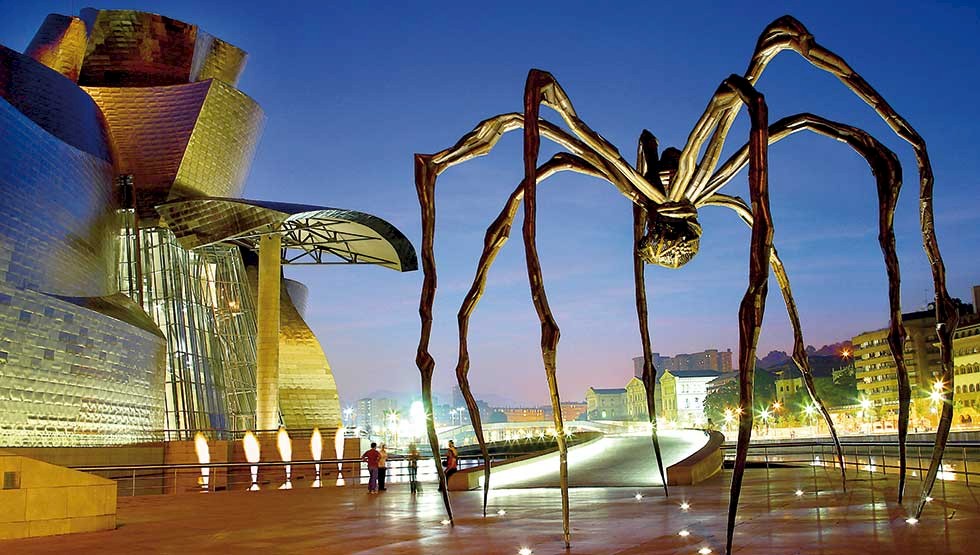

Inside, the gigantic iron coils of sculptor Richard Serra’s work The Matter of Time welcome visitors into a highly original artistic experience. Part-labyrinth, part-space station, the Guggenheim Bilbao is as unique inside as it is on the outside. Belonging as it does to an international constellation of museums, the Bilbao art house has access to the extensive permanent Guggenheim collection. These works, including works by Andy Warhol and Mark Rothko, as well as Louise Bourgeois’ giant arachnid Maman on display outside the building, complement one another and, together, offer an in-depth, expanded view of modern and contemporary art. Besides the star-studded collection, hit exhibitions by artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly and Anish Kapoor have kept people coming back to marvel at Bilbao’s modern landmark.

For Alfonso Martinez of the BM-30 think-tank, founded in 1991 with the goal of fostering social, economic and urban renewal in the Bilbao area, the main factor behind Bilbao’s remarkable transformation was fear of a bleak-looking future. “You can call it need or whatever you like, but I like to call it the fear factor. Fear creates leaders. Leaders arise at times of social fear and uncertainty. Fear is not negative. Self-complacency is negative. A leader works with other leaders to create a plan for the future.”

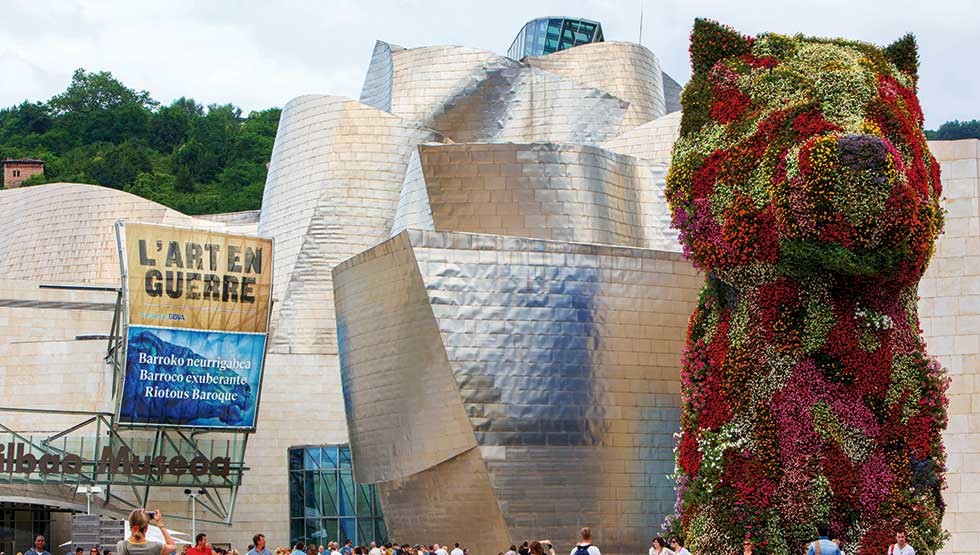

And the Guggenheim is nothing if not a bold statement of leadership. “The Guggenheim is like an alien in the middle of Bilbao. But Jeff Koons’ Puppy flower sculpture, which sits outside, gives it meaning. It attracts children to the museum, and children are the drivers of innovation, because they are unafraid of change,” Martinez concludes.

“The Guggenheim is like an alien in the middle of Bilbao. But Jeff Koons’ puppy flower sculpture, which sits outside, gives it meaning”Tweet This